This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

28/04/2017

Think City Malaysia – World-Class Placemaking

Giles Semper tells us about his experience in Malaysia meeting Placemaking Agency ‘Think City’

At the beginning of April 2017 I was lucky enough to spend time in Kuala Lumpur with Jia-Ping Lee and Joanne Mun of Think City, the Malaysian placemaking agency.

Think City was founded in 2009 to play a role in the revitalization of Georgetown, the capital of Penang and a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2008. Think City is not part of government, but rather a subsidiary of Khazanah, the country’s sovereign wealth fund. It also has a partnership with the Aga Khan’s Cultural Trust and Project for Public Space. It is seeking to make itself sustainable by attracting third-party funding from organisations such as Citibank’s City Foundation.

Think City has gained a reputation as a genuinely ‘bottom-up’ organisation, growing – as it did – out of a programme of small community-led placemaking interventions. In its first years it established and managed the RM 20 million George Town Grants Programme (GTGP) which sought to address endemic urban problems. It is also playing a key role in protecting Malaysian cultural icons such as Fort Cornwallis. It has the personality of a classic third-sector organisation, putting stakeholders together to achieve lasting change.

In 2014 Think City expanded its work to include Kuala Lumpur, focusing on a 1km radius from the city’s mosque Masjid Jamek. Describing the context of this work, Jia-Ping and Joanne described how the traditional ‘shop houses’ that form the historic core of Kuala Lumpur are at risk. Family units in Malaysia is generational and the traditional shop houses are no longer suitable to accommodate them. Longstanding residents have disappeared in a familiar pattern of ‘suburban flight’.

Furthermore the Rent Control Act was repealed in 1997, meaning that the rents on heritage dwellings in the city skyrocketed, and the buildings became a target for investors. In Kuala Lumpur the buildings do not have the same level of UNESCO-inspired protection as in Georgetown and have been inappropriately adapted or even demolished.

The terms of Think City’s grant programme are broad and liberal. Applicants for the RM10,000 to RM100,000 grants can be drawn from almost any sector as long as – in Jia-Ping’s words – they ‘bring the end-user point of view’. Think City will fund both revenue and capital projects, including restoration of buildings, improvement of public spaces, urban mobility projects and cultural activities. (18 grant programmes are now underway in Kuala Lumpur with 9 completed). Grantees have to complete their draw down of the grant in 18 months. Refreshingly Think City eschews the all-consuming ‘KPI Culture’. Rather, in Jia-Ping’s powerful phrase: ‘Not everything that can be counted, counts.’

The terms of Think City’s grant programme are broad and liberal. Applicants for the RM10,000 to RM100,000 grants can be drawn from almost any sector as long as – in Jia-Ping’s words – they ‘bring the end-user point of view’. Think City will fund both revenue and capital projects, including restoration of buildings, improvement of public spaces, urban mobility projects and cultural activities. (18 grant programmes are now underway in Kuala Lumpur with 9 completed). Grantees have to complete their draw down of the grant in 18 months. Refreshingly Think City eschews the all-consuming ‘KPI Culture’. Rather, in Jia-Ping’s powerful phrase: ‘Not everything that can be counted, counts.’Jia-Ping and Joanne described how the grants approach was designed to crowdsource projects from the community in a country where residents have not been encouraged to used to perhaps has its roots in the fact that Malaysia never had to fight for its independence. Education in the country also tends to be prescriptive, without dialogue. Younger citizens, however, understand the Think City approach and are participating.

We met in Kuala Lumpur’s evocative art deco Central Market. Formerly a wet market, the building now houses stalls selling Malaysian arts and crafts. Our tour took us past some of Think City’s projects. We followed the route between the two rail stations – Pasar Seni and Masid Jamek. This took us through the heart of the downtown area and included an attractively-landscaped square on the street Jalan Tun HS Lee.

We arrived at the Old Market Square on Lebuh Pasar Besar. This is a space that Think City has been seeking to animate with a series of events, including a hugely-popular designer T-shirt festival.

Our journey continued past some construction sites linked to the ‘River of Life’ (http://www.aecom.com/projects/river-life/), one of Malaysia’s Economic Transformation Programmes. The USD1.3 billion project has three elements – river cleaning, river master-planning and beautification. It spans across the meeting point of three city rivers (giving the city its name – ‘muddy confluence’!) with a total area of 781 hectares and 63 hectares of water. It will reconnect the city back to the river, creating an exciting and high-value waterfront. The numbers of predicted new residents and jobs are simply staggering.

Our journey continued past some construction sites linked to the ‘River of Life’ (http://www.aecom.com/projects/river-life/), one of Malaysia’s Economic Transformation Programmes. The USD1.3 billion project has three elements – river cleaning, river master-planning and beautification. It spans across the meeting point of three city rivers (giving the city its name – ‘muddy confluence’!) with a total area of 781 hectares and 63 hectares of water. It will reconnect the city back to the river, creating an exciting and high-value waterfront. The numbers of predicted new residents and jobs are simply staggering.Our next visit was to the Masjid Jamek rail station – surely one of the busiest in the capital. Here Think City has set up a stage in the station’s concourse. It accommodates a thriving programme of music and theatrical performance – some traditional, some contemporary. Think City has appointed its own events co-ordinator to oversee delivery.

Kuala Lumpur boasts some of the finest art deco buildings in Southeast Asia constructed at a time when export sales of Malaysia’s then-two natural resources – tin and rubber – were at their height. Several of them have benefited from façade improvements funded jointly by the city, the owners and Think City, with many more to follow.

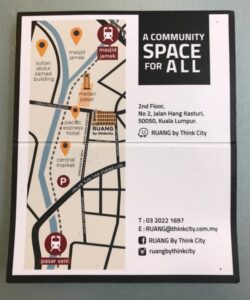

We adjourned to one of these buildings ‘Ruang – A Community Space for All’ on 2 Jalan Hang Kasturi. Think City has refurbished this floor as a hub for arts and community uses, and it is thriving – particularly at weekends. Jia-Ping, Joanne and their colleague Solomon talked me through some other Think City-funded or inspired projects, including a mapping of restaurants that serve local vegetables in KL by Eats, Shoots & Roots (http://eatsshootsandroots.org/), a project mapping mentions of the area in literature called Literacity, and House Vision – a project by Kenya Hara, the founder of Muji to reimagine living space in KL, with the participation of local architects.

In each case Think City works hard to support organisations through the process. While avoiding the dreaded KPIs, the funder seeks to measure the benefits to communities, the ‘quality of knowledge’ forthcoming and the ease of implementation. Much like UK funders, Think City looks at both the outputs and the outcomes of any project, using its own ‘Logical Framework’ approach.

In each case Think City works hard to support organisations through the process. While avoiding the dreaded KPIs, the funder seeks to measure the benefits to communities, the ‘quality of knowledge’ forthcoming and the ease of implementation. Much like UK funders, Think City looks at both the outputs and the outcomes of any project, using its own ‘Logical Framework’ approach.Now, with its first three-year term of activity nearly completed in KL, Think City is putting in place its strategy for the next period. It is considering creating a ‘Creative-Cultural District’ for the city centre. It is also seeking other funders to partner in delivering the grant programme.

Inspired by Think City’s flexible, responsive and inclusive approach to placemaking, I headed off into the hectic and congested KL downtown. As drops of warm rain began to fall, announcing the daily tropical storm, I ducked into the Pitstop café back on Jalun Tun HS Lee. This is a social enterprise with a ‘pay what you can’ Bubur Bar (rice porridge and a dessert) feeding and retraining homeless people. How nice to find that Think City funds the education part of the project.